A girl with Dyslexia

My role: Photographer

Social Teaser Video

My role: Recorder and editor

Audio Story

Photo Gallary

My role: Photographer and editor

Anita Kuttenkuler, left, tutors Kierstyn Lawson (cq), 10, in her home on Tuesday, April 18, 2017 in Jefferson City, Missouri. Kuttenkuler is retired and she has been tutoring children with dyslexia for five years. She became a Master certified dyslexia tutor in 2014.

Dyslexia tutor Anita Kuttenkuler teaches Kierstyn Lawson (cq), 10, how to spell words in a different strategy in her home on Tuesday, April 18, 2017 in Jefferson City, Missouri. Kuttenkuler works with Kierstyn to help her spell and read, problems Kierstyn struggles with because she is dyslexic.

Kierstyn Lawson (cq), 10, holds a certification she received for completing a new level of reading and spelling exercises in her tutor’s living room after class on Tuesday, April 18, 2017 in Jefferson City, Missouri. During her sessions with her tutor Anita Kuttenkuler, Kierstyn also enjoyed the company of Kuttenkuler’s dog Sadie.

Anita Kuttenkuler, left, tutors Kierstyn Lawson (cq), 10, in her home on Tuesday, April 18, 2017 in Jefferson City, Missouri. Kuttenkuler is retired and she has been tutoring children with dyslexia for five years. She became a Master certified dyslexia tutor in 2014.

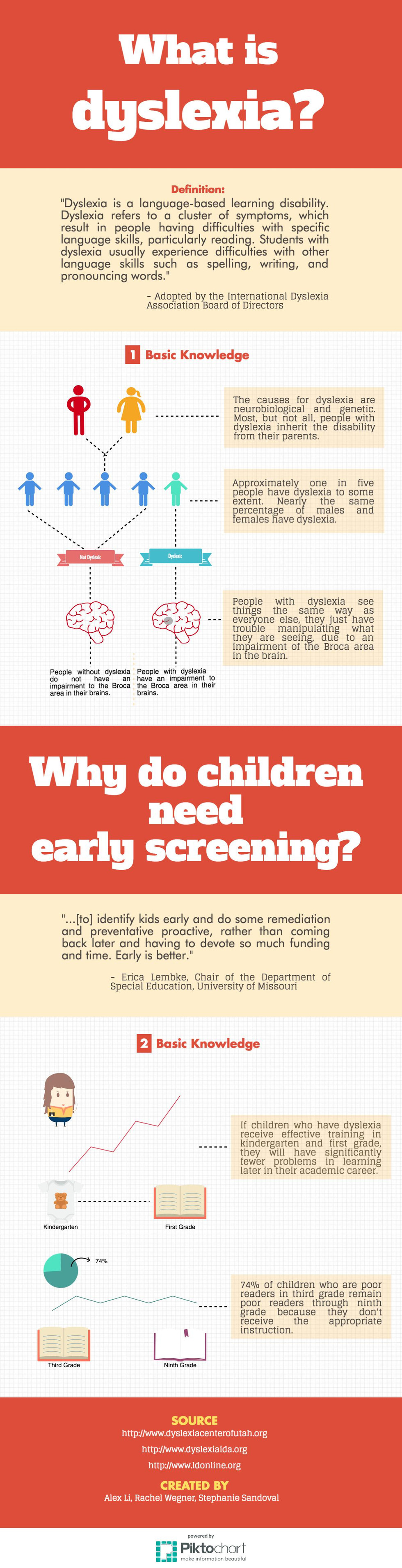

Infographic

My role: Creator

Text

My role: Associate writer

Falling through the cracks: The dilemma of a dyslexic kid

By: Alex Li, Rachel Wegner, Stephanie Sandoval

COLUMBIA — When Anita Kuttenkuler first started teaching she had never heard of the word “dyslexia” before, even though she probably had at least one dyslexic student in her classroom.

Kuttenkuler was a Title I reading teacher for 15 years, but for the past 11 years, she has worked as a certified dyslexia tutor. When she taught as a Title I reading teacher, she had a group of kids who weren't making as much progress as the others in her class. She used everything she was taught and everything she knew, but it still didn’t work.

Little did she know at the time, those students had dyslexia. According to the Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity, 1 in 5 students struggle with the condition.

“I knew they were smart, and I knew that it wasn’t that they weren’t trying,” Kuttenkuler said. “And so I started learning.”

While some people may think having dyslexia means merely seeing numbers and letters differently, the learning disability is actually a genetic trait or neurological condition that affects how a person’s brain functions. Some Missouri schools don't have an effective way to help students with this disability, and others don't have a way to help at all. A new state mandate, however, is looking to change that.

The state law mandates all schools begin providing dyslexia screenings at the start of the 2018 school year. But the screenings won't be funded by the state, leaving it up to the schools to cover the costs.

A task force assembled by the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) is working to keep costs as low as possible. Erica Lembke, a member of the task force, said they hope to keep it as low as a few dollars per student.

Students with dyslexia can receive accommodations through schools, but only if they meet certain standards. To receive these accommodations, they must qualify for special education or an Individualized Education Program (IEP). However, not everyone qualifies for an IEP, those who don’t qualify get assigned a Title I reading teacher like Kuttenkuler.

Due to some schools’ lack of knowledge and resources on dyslexia, teachers are still left with unanswered questions as to why their students learn at a slower pace.

“I just didn’t know what it was at the time, because I’ve never been taught,” Kuttenkuler said.

And some schools still don’t have a plan to answer these questions.

Some districts already have screening and intervention methods in place for students with dyslexia. The California R-1 School District shortened its class periods by a few minutes each to carve out 30 minutes a day for dedicated instruction of students who need extra help in areas like reading and comprehension. Instead of creating a new fund, this plan reallocated their existing budget to add support for students in need.

Since the task force is still developing recommendations for the new screenings, California school district Superintendent Dwight Sanders said their 2018-19 budget remains uncertain.

“We're fiscally sound as a district, but at the same time, if we continue to see expectations come that carry with them a price tag, and we don't have any additional funding provided by the state or federal government, something has to give eventually,” Sanders said.

Kierstyn Lawson, 10, is a student at California R-1 Elementary School. She was diagnosed with dyslexia in January 2016. Kierstyn’s mom, Stephanie Lawson, knew her daughter was struggling in school since kindergarten, but didn’t know why.

“I would tell her what one word was in the middle of the page and then by the time we get to the end of the page, that same word would be repeated and she wouldn’t know what it was,” Lawson said.

When she was diagnosed, Lawson thought this would open opportunities within the school, but she thought wrong.

“It was almost like the school didn't want to accept the diagnosis,” Lawson said. “After meeting with them, they had to run their test — the IQ testing — to see where she fell. Because, in order to qualify for an IEP, you have to be below average IQ, which I didn't think she would qualify for. She's a bright kid, so she obviously was above average on her IQ testing, so she didn’t qualify for an IEP.”

The problem with IQ tests? A student can have a high IQ, but still have dyslexia, not allowing them to qualify for IEP… like some of Kuttenkuler’s students.

“I have a couple of kids that are actually in the gifted program but have trouble reading and spelling,” Kuttenkuler said. “They’re brilliant, but they have to learn it a different way.”

This disconnect and inability to access the proper resources prevents students from unlocking their full academic potential.

“And we want to get them before they quit because that IQ,” Kuttenkuler said. “They’re really smart, but we make them feel really dumb.”

Lawson said early screening would have helped Kierstyn. She also explained a need for greater education about what dyslexia is and how to help these kids.

“When I was going to school, you didn’t really hear of dyslexia, or you just thought dyslexia was letter reversal when you were writing,” Lawson said. “It’s how the brain is helping that kid process what they're seeing on the page, and I think there needs to be a bigger education about what dyslexia is and how to help these kids.”

Without the proper education or resources to identify dyslexia early on, kids like Kierstyn have a greater risk of slipping through the cracks.